Human-level Trick-Taking Card Game AI

Leveraging reinforcement, imitation, and supervised learning to beat humans at Judgement, a playing card game which I’ve played far, far too much of (repository here - try your hand at beating the bot!), with applications to general trick-taking games.

1. Background: The League of Judgement

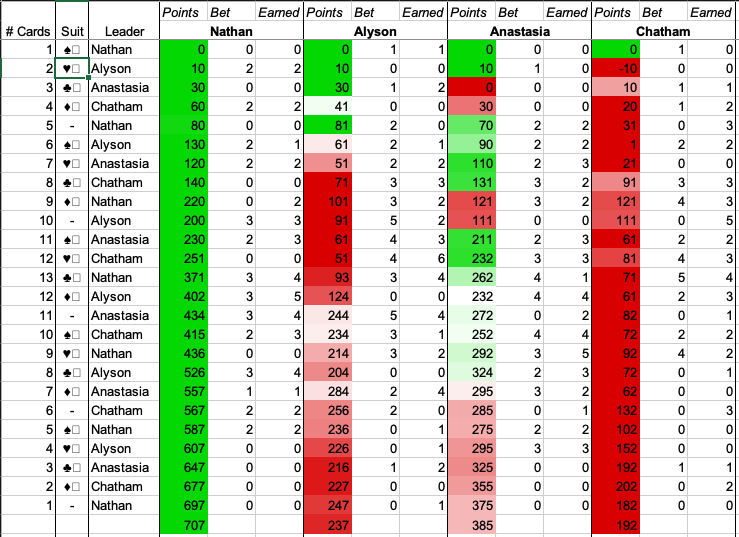

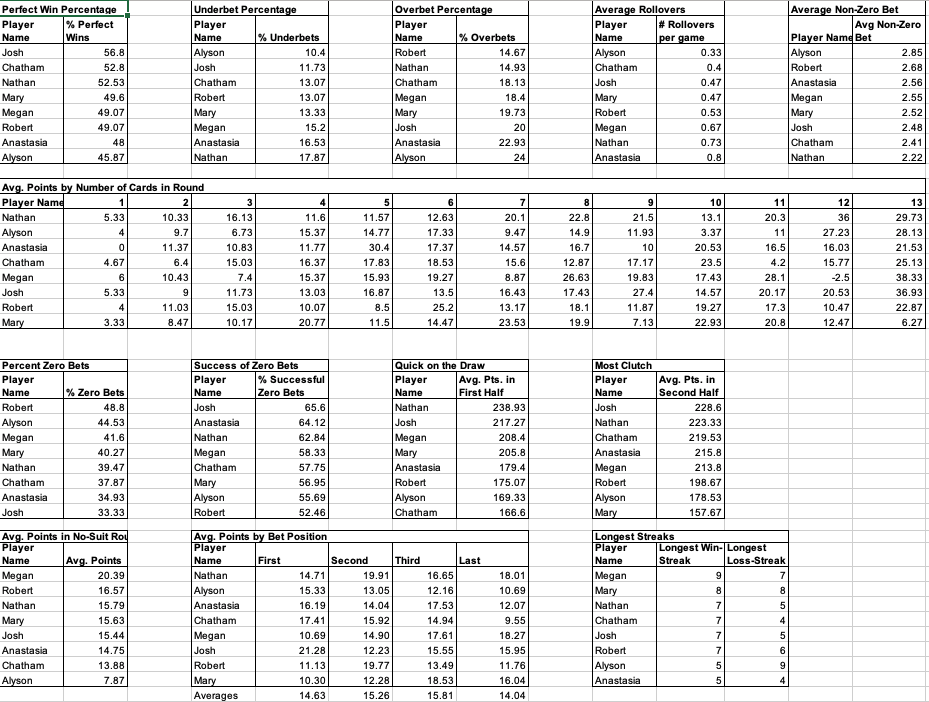

Over my college career, I played a LOT of the trick-taking card game called Judgement/Kachufool (rules here). An embarassing amount, almost. So much so that I developed an entire software based infastructure around the game, including automated scoring:

advanced statistics (and there about 25 more stats not in this screenshot):

and an entire league system complete with seeding and playoffs, where eight of my friends and I played dozens of games of Judgement at locations as varied as coffee shops, the laundry room, and of course IHOP:

After all this effort and the heights of competition that were reached in the Judgement League, it was only natural that I would try to use computers to defeat my friends at the game.

2. Structure of a trick-taking game

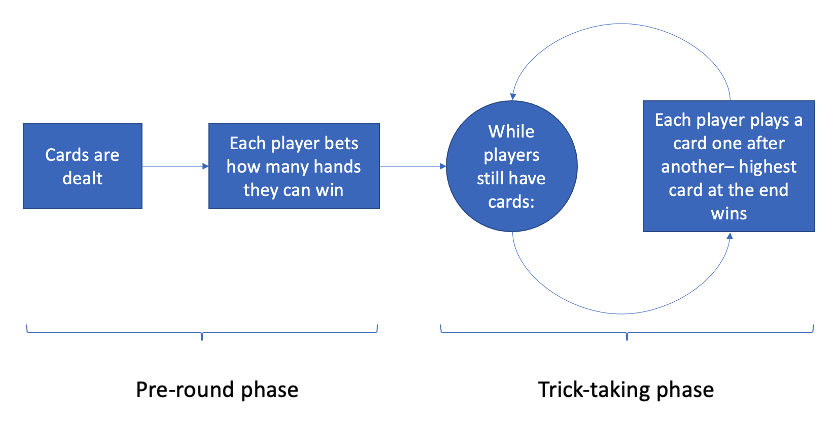

Judgment, and trick-taking games in general, can mostly be separated into two distinct phases - the pre-round phase, and the trick-taking phase.

As shown in the flow chart above, in the pre-round phase, cards are dealt and the player bets how many hands they think they can win. Once all bets are determined, the players then actually play out the rounds, trying to win exactly as many hands as they predicted while preventing other players from doing so.

Critically, these two phases are completely separable. This allows us to train models for each phase separately, with each individual problem seeming far more tractable.

The pre-round phase takes the form of a bread-and-butter machine learning problem - as input, the model gets a hand of cards, other player’s bets, etc., and as output it simply returns an integer corresponding the number of cards to bet. The trick-taking phase is a bit more difficult for a machine learning system, requiring inputs of a hand of cards, the cards already in play, the cards that have already been played, etc., and having effectively 52 outputs (a card to play).

With a clear path forward, it remained to figure out the many, many details of such a project. How would I obtain data? How would I architect the networks? How would I set up the training process?

3. Data, Data, Data

As with almost all projects in ML, the first bottleneck was training data. While my spreadsheet captured enough information to develop detailed performance statistics, it didn’t record the critical data needed about what cards players had in their hands when they were making their decisions - I needed to obtain this data some other way.

As a AlphaGo fan, I was of course tempted to use pure RL and self-play to brute-force a sensible policy. Given my extremely limited compute, though, I was not quite naïve enough to believe that would work. I would need to get more creative.

Simulating games

The first order of business would be to create a simulation environment within which to simulate an arbitrary number of games of Judgement. Within JudgmentGame.py, I encoded the rules of the game and the architecture to ask for bets and moves from multiple agents and simulate out an entire game. Within JudgementAgent.py, I created the default class which would provide the structure that a Judgement agent would need to have to interact with a JudgementGame object and declare it’s bets and moves.

On top of this foundation, I would be able to create and evaluate custom Judgement agents. I also built the infrastructure to save the inputs and eventual results of each of the decisions that an agent made, so that this could be saved and later used in reinforcement learning.

Generating trick-taking data

While the structure of the machine learning problem for the trick-taking phase is far more challenging, in a way it was easier to collect data for this phase.

Judgment is a game that is relatively amenable to a heuristic policy for actually playing cards. The heuristic algorithm implements a very bare-bones Judgement playing strategy, similar to a beginner player. If the agent has not yet reached its goal, it will try to win the round by playing the highest card possible, unless it cannot win, in which case it plays the lowest card possible. On the other hand, if its goal has already been reached, it attempts to lose the round with the largest card possible.

By running this heuristic policy for thousands of games in my simulated environment, I could generate an arbitrary amount of input-output data to use in imitation learning later.

On top of this foundation, I wrote entirely random betting and card-playing algorithms, as well as a simplistic betting algorithm and a simplistic card-playing algorithm to which aim to be slightly better than random.

Generating betting data

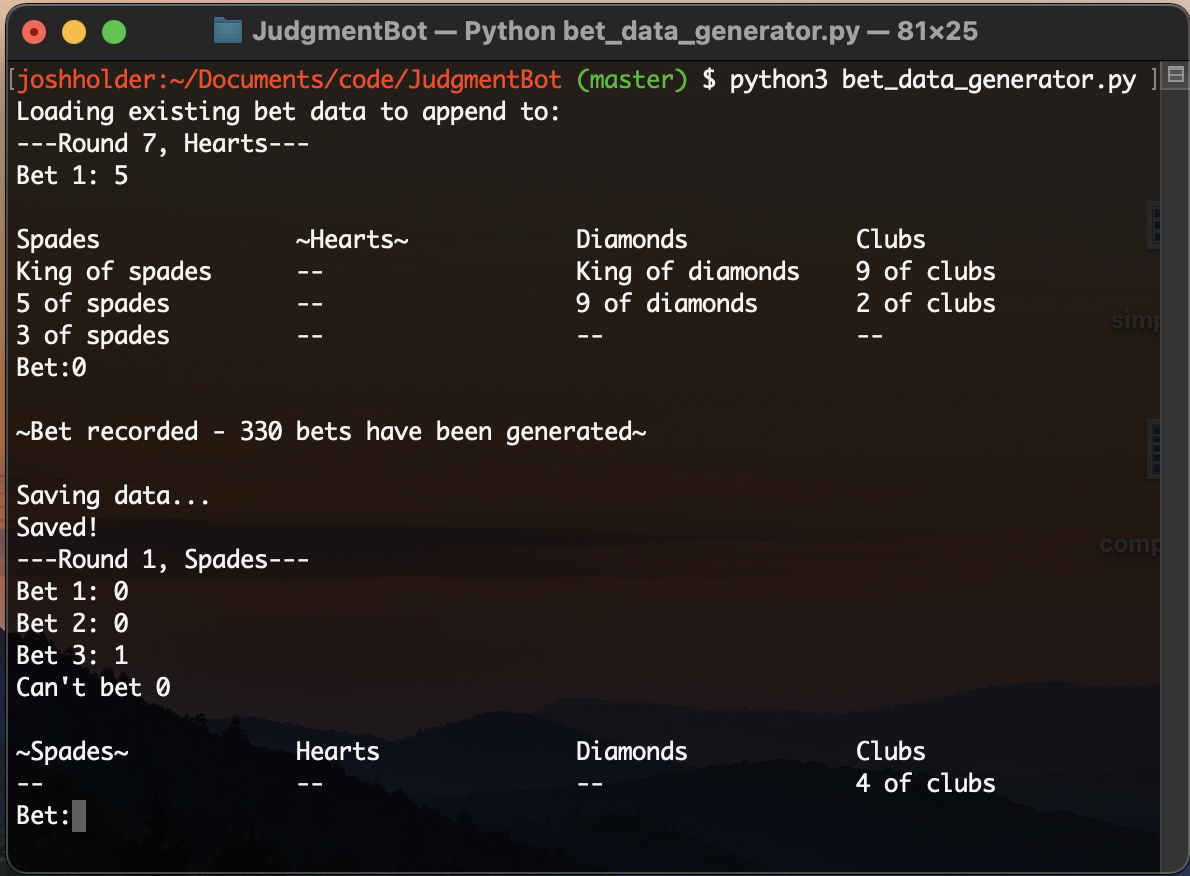

Although the betting machine learning problem is simpler, it’s far harder to develop a heuristic policy (in fact, this is where much of the strategy of the game comes in). I needed to find a way to get human data on bets.

Luckily, I had a captive audience of Judgement-obssessed friends to serve as data-collection drones - all I had to do was write provide them the tools. I wrote some code which could generate sensible-seeming Judgement situations and hands (not as easy as it sounds - see bet_data_generator.py), wrapped it in a clean UI, and recruited some friends to use the UI and bet as they would in a real game.

For a few weeks my friends would crank out Judgement bets in their free time (Robert Alexander and Alyson Resnick were especially prolific) and send me their data to be used in training the AI. By the time the semester ended, I had a few thousand bet situations saved, and could begin training in earnest.

4. KEY INSIGHT: Unique NN Architecture

With a large amount of data collected, and a plan to acquire much more, I began architecting the actual structure of the neural network models.

Pre-round phase model

Betting comprises a large part of the complexity of the game. At the start of every round of Judgement, the player is dealt a hand of cards, and based on this hand of cards, needs to respond with a number of hands they think they can win. For example, if the player has all Aces (a high card), they might expect to win a higher number of rounds than if they have all 2s, a low card.

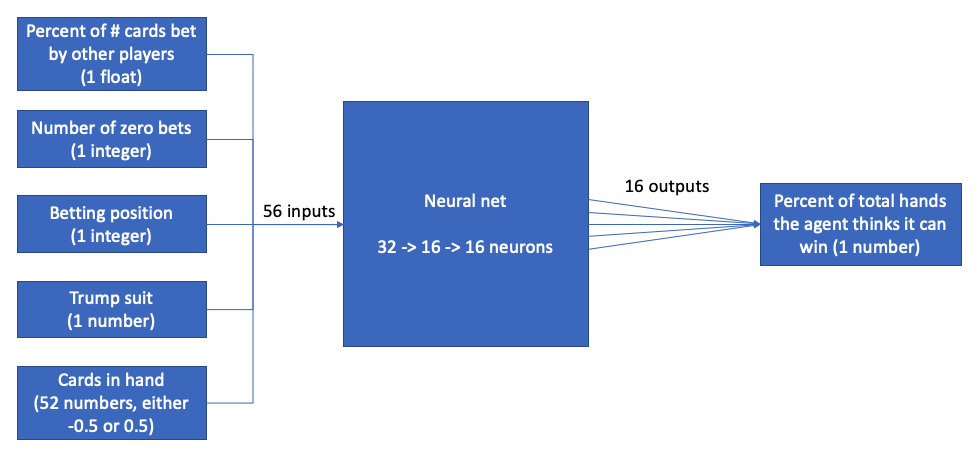

In simple terms, as input, you have a set of cards, and as output, you have a single integer. This is a textbook classification problem, and thus a standard neural network is a perfect choice for this algorithm - the architecture writes itself! In plain english, the architecture input/output relationship should look something like this:

Rather than using something like a RNN to handle variable amounts of previous bets, we simply add all previous bets together and take it as a percentage of the maximum, being sure to also feed the network the number of zero bets directly. This bakes in a certain amount of human knowledge into the network (i.e. zero bets are uniquely important) and makes it harder for the agent to learn behaviors like “hate-betting,” but greatly speeds training. Layer sizes were chosen with trial and error, aiming to strike a balance between overfitting, computational speed, and expressiveness.

Trick-taking phase model

In my opinion, the critical insight of the project lies in the design of the trick-taking model, and is the secret of its success in the face of extremely limited computational resources. A naïve model might simply play all its cards one after another, receive its rewards at the end of the round, and perform RL updates on this information.

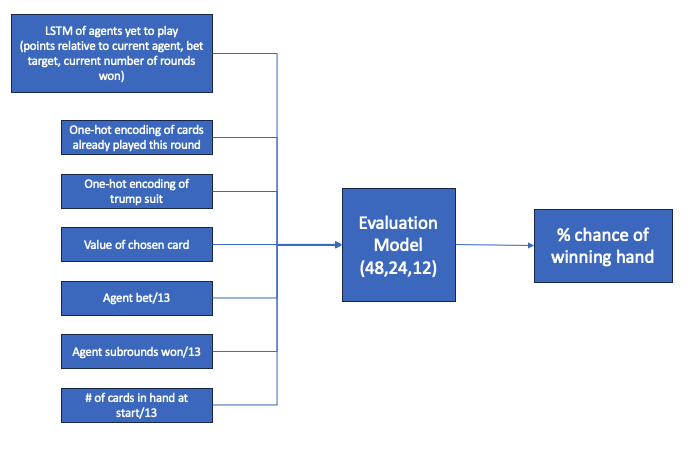

This would, however, be a mistake: trick-taking card games provide a rich source of feedback which comes each and every time you play a card, not just at the end of the round - namely, did you win or lose the hand! Often in Judgement, you have a clear idea of whether you want to win or lose a specific hand - the skill emerges when you have to predict what card will achieve this for you.

Therefore, in addition to a “what card to play” model (action model), we can create an intermediate “evaluation” model which determines, given a certain card is played, the likelihood of winning the round with that card. Given the high frequency of feedback (~676 data points per game simulated, compared to 100 scoring and betting events per game), this model can quickly become very highly predictive. This information is invaluable to the larger model, and in effect allows the action model to skip having to learn this critical predictive model on its own.

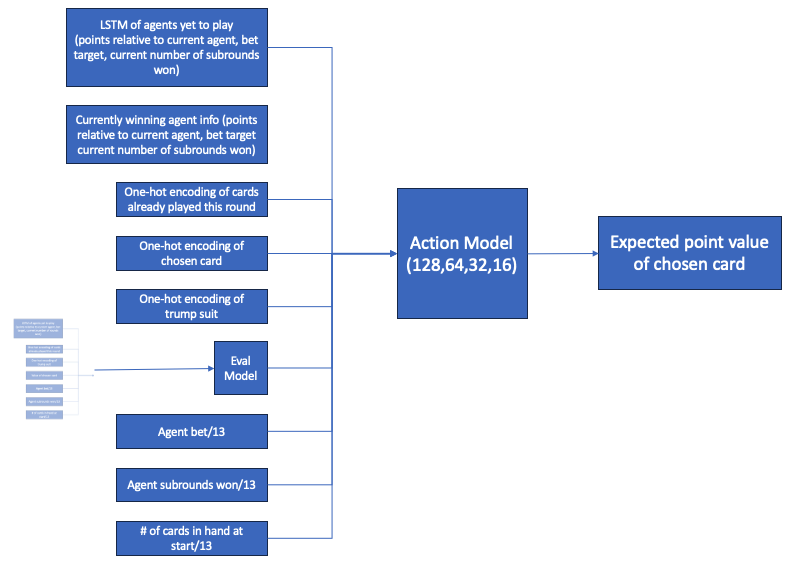

The other significant nuance is how to deal with information on other agents. This information (points scored, their target bet, how many hands they’ve won thus far, what cards they’ve already played) is clearly critical to the decision of what card to play, but determining the best represenation for this information is difficult because the number of agents going before and after the current agent is variable. For example, if the agent is going first, the length of list of agents who have already played is 0, but the length of the list of agents yet to play is 3 - this changes as the position of the current agent changes. To handle this variablity, we use an LSTM structure for the agents yet to come.

Thus, the architecture of the action model is structured as follows:

In order to choose a card to play, an agent calls the action model on each feasible card to play in the hand (which also calls the evaluation model as a byproduct), and selects the card which returned the highest expected value out of the model.

5. Training: RL, SL, and the Kitchen Sink

It was now time for the training process. Again, due to limited compute, I used the groundwork I had laid to bootstrap the model to a reasonable starting point before attempting to use end-to-end reinforcement learning.

Bootstrapping policies with supervised and “imitation” learning

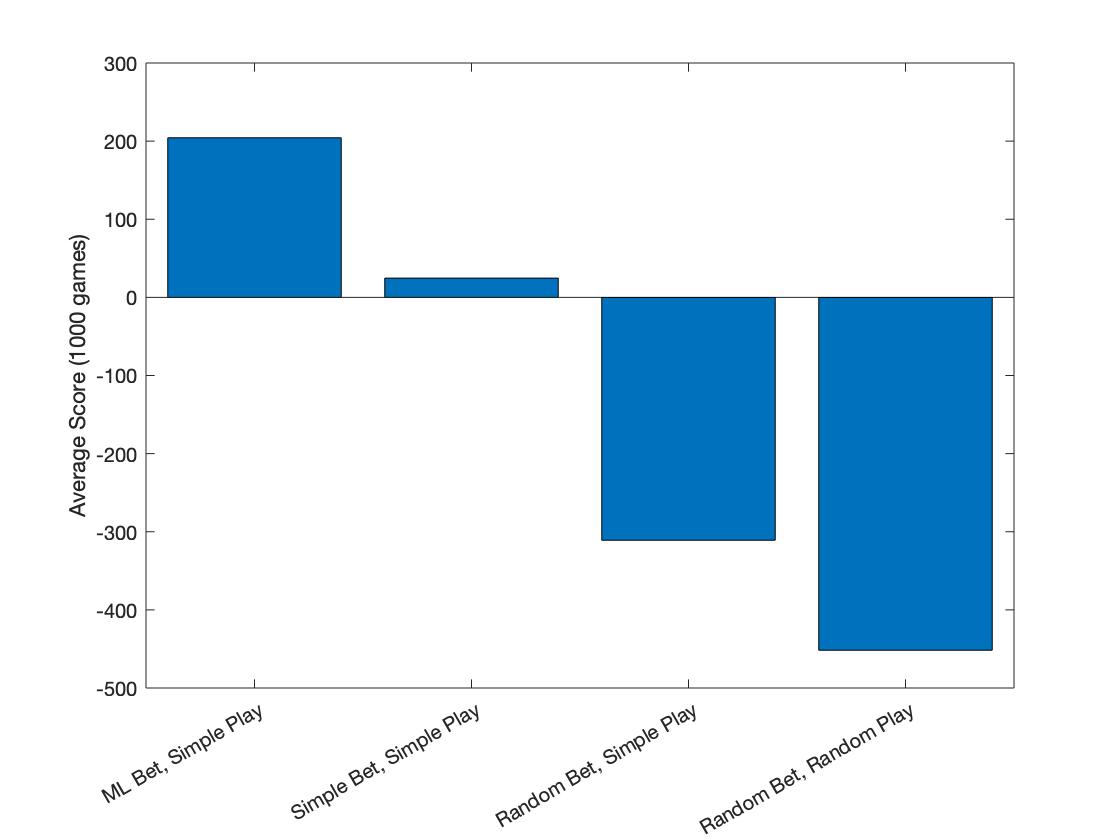

To bootstrap the betting model, I set up a simple supervised learning pipeline on the human-collected data. This was shockingly effective - by combining the ML betting model with a simple trick-taking policy (the heuristic algorithm), I could blow other agents out of the water and score around 200 points, a respectable score for humans (albeit against significantly weaker opponents).

To pretrain the action and evaluation models, I implemented the simplest possible version of imitation learning - I simulated several thousand games of the heuristic policy + the bootstrapped betting model, collected data, and then trained the initial action and evaluation models in a supervised fashion on the collected data.

Self-play

After pretraining, I had an agent with performance similar to the ML Bet + Simple Algorithm from the previous chart. Critically, though, the action policy was now a neural network, and thus had the potential to become far better with further training. To go beyond the heuristic policies towards a policy that could be truly human level, I had no other options but to turn to pure reinforcement learning and self play.

I was aware that this would be a highly challenging learning environment:

- In multiagent settings, there can be possibly infinite Nash Equilibria, making local minima more worrisome. Self-play in this scenario might converge to a strange meta which doesn’t translate to the meta associated with human play.

- By training three networks at once, training would be slow, and the optimization environment would likely be extremely challenging. Gradient updates in one of the three networks could counteract updates in another network

- Due to simplications in the network architecture, the agents wouldn’t have access to all the same information that human players due, inherently limiting the ceiling of performance

Despite this though, I decided to push ahead and see how far I could get.

My first attempt was DQN - implementing the necessary data pipelines, replay buffers, gradient updates, was a level of software engineering my Mechanical Engineering training did not at all prepare me for. I have a newfound respect for data scientists and viscerally understand statements to the effect of “the hard part of machine learning is wrangling data.” Eventually, though, I was able to get training up and running (dqn_train.py) and started seeing significant score improvements.

However, I ran into a persistent issue throughout the training, which was that DQN necessitated a high computational load, memory, and RAM requirement to fit the entire replay buffer in memory - I continually had to reduce the size of the buffer and make other compromises, and felt that this was hindering performance. At a certain point in development I had the bright idea to switch from TD-learning style updates to Monte-Carlo estimates of rewards. My thinking at the time was that this would reduce the size of my replay buffer, provide more accurate ideas of my rewards, and reduce computational load by reducing calls to the action model. It did have the effect of speeding training and reducing memory requirements, but perhaps unsurprisingly, I soon began to run into issues with gradient explosion which were frustratingly stubborn. (This stackoverflow post, which I discovered later, provides a compelling explanation for why this bright idea may not have been so bright.)

Not knowing how to fix this at the time, I decided to shift to a A3C approach to training, which would hopefully increase training stability, remove the annoying memory requirements for the replay buffer, and allow me to take advantage of greater parallelization. After implementing this (a3c_train.py), the gradient explosion issues were gone due to the increased stability from taking training data from disparate parts of the state space, but training simply refused to improve further.

Here, I started to deeply relate to perhaps the most famous RL blogpost. RL truly is hard, and most infuriatingly, provides little signal as to why things aren’t working when performance refuses to improve. I flailed around for quite a while, tried different evaluation metrics, hijacked my lab computer’s GPU, and yet the agent was still firmly stuck. I still have a plethora of ideas of how to further improve performance, but wanting to move onto other personal projects, I decided to simply see if I could quantify just how far the self-play had gotten me and get some closure.

6. Testing the AI

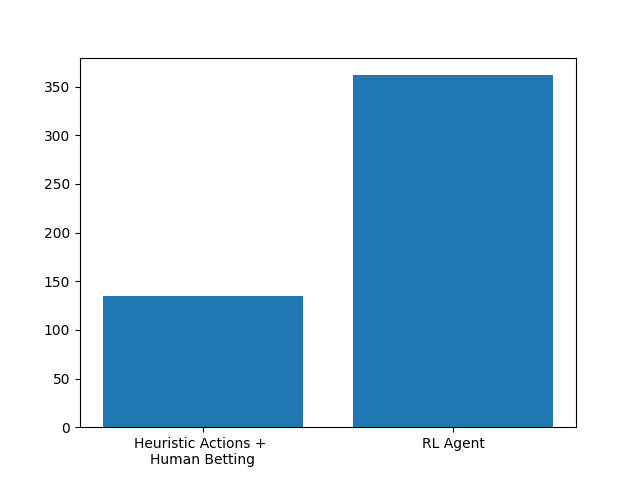

First, I tested this algorithm against the heuristic agents previously mentioned.

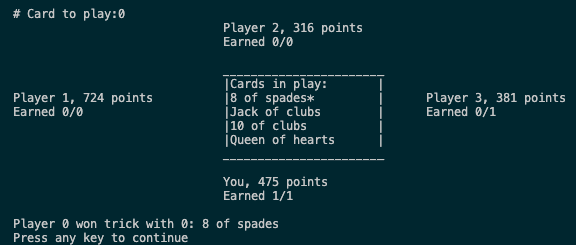

Clearly, the RL-trained agent blows the agent it was trained on out of the water, showing clear improvement from the bootstrapped solution. It’s all well and good to beat the training data, but I knew I wouldn’t be satisfied unless the bot could beat me. Thus, I played a few games - although I did manage to win my first two games against the bot, it performed respectably. And in the third game, it finally happened:

It beat me, and with an extremely impressive score of 724! Although the policy is still inconsistent and likely exploitable, scoring 700+ points and outperforming a human player is no small feat, and demonstrated significant understanding of the mechanics and strategy of Judgement. After over a year of work, I finally feel satisfied.

7. Towards Superhuman Performance

Despite having the ability to beat an experienced Judgement player on a good day, the bot is still far from superhuman performance. I have several ideas for further improving performance, which I may or may not attempt in the future.

- Buy a GPU and train larger models, for longer! This would allow me to use larger replay buffers and true TD-learning updates to see how far I can push DQN.

- Implement true MARL strategies, rather than applying naïve single agent RL training approaches to the multi-agent setting

- Rather than RL, use counterfactual regret minimization as was used to achieve superhuman performance in multi-agent poker

- Try new training methods - perhaps it’s best to train each model one at a time in sequence. This could improve stability because when gradient are updates are made w/r/t one model, behavior of other models is consistent

- Increase the amount of information available to models (although this would also require significant increases in computing resources).

Overall, this was a fantastic excuse to level up my software engineering, machine learning practitioner, and Judgment-playing skills. One day, I’d love to apply these ideas to develop an AI which is superhuman not only at Judgment, but at all trick-taking card games.