Breaking the SPL-T World Record

An obsession with finding the optimal strategy for a simplistic puzzle game leads me through an exploration of various fields of computer science. After countless hours and applying knowledge of parallelization, optimization, human-AI collaboration, and even reinforcement learning, I managed to wrest the world record (1196 splits, 1208 w/ human assistance) first from Craig of flashingleds.net, and then from @mangosquash and cement my legacy in extremely niche puzzle game history. (repository here)

1. Beginning of an obsession

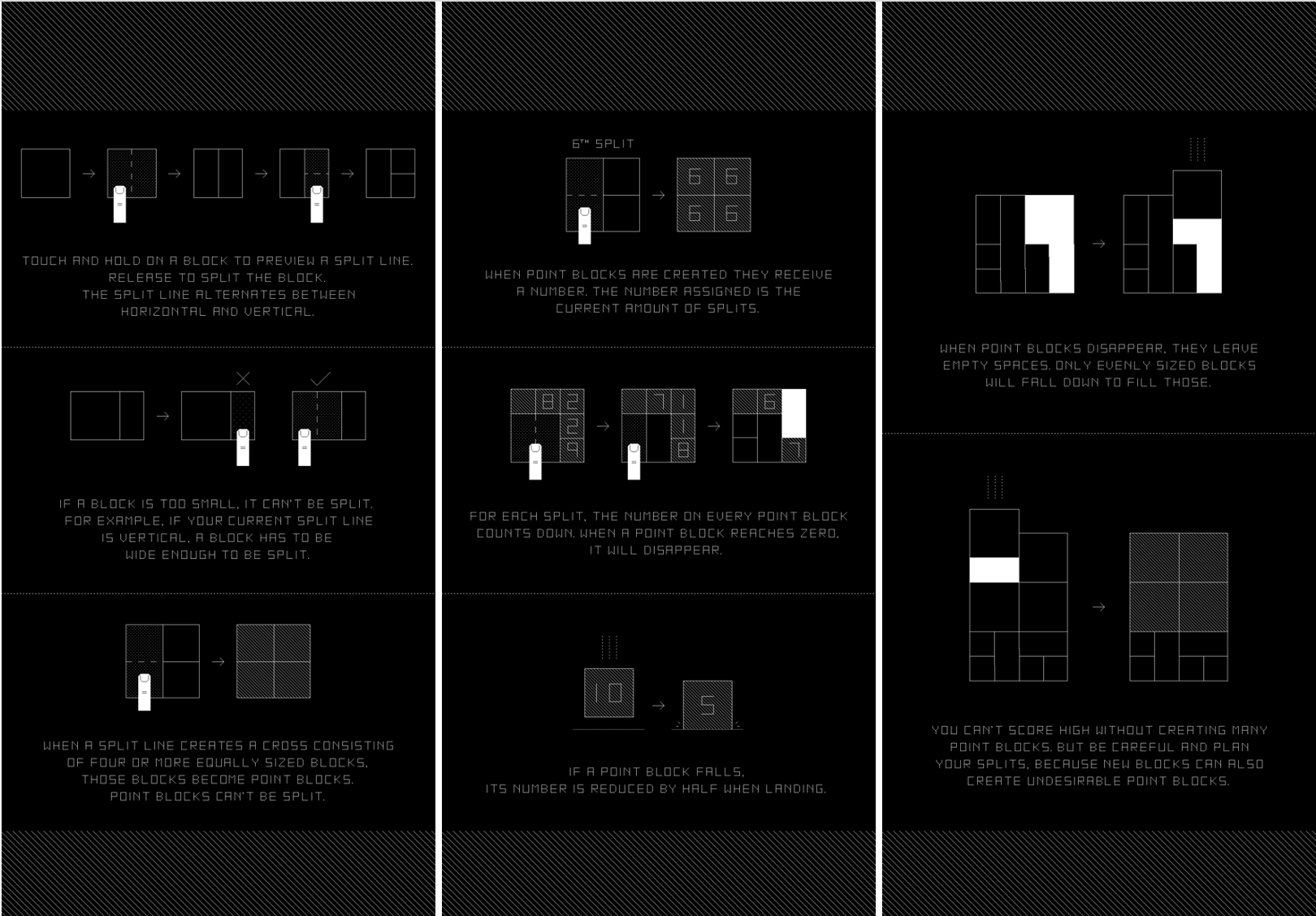

In 2016, I downloaded an unassuming puzzle game by the name of SPL-T. It has everything I love in a puzzle game - a minimalistic yet beautiful design, and a simple concept which yields surprising complexity. To really get the most out of this post, you should download the game and play for a bit, watch this quick rules primer, or at least glance at some screenshots from the tutorial below:

As in any good puzzle game, the fun emerges when you hit a wall and need to really brainstorm how to take your strategy to that next level, and there are plenty of walls to overcome in SPL-T. At this time, I completed this process a few times, got to a respectable score of 539, and gradually lost interest.

Fast forward to Fall 2019, and a very different version of Josh rediscovered the game. Having taken some computer science courses at Rice, my mentality on the game was completely different. In a game with no randomness, there had to be a strictly optimal sequence of moves, hiding in the massive search space, that led to the highest possible score. The more I thought about it, the more this bugged me. How hard could it be to find this optimal solution? (Spoiler: it could be hard. Very hard.)

2. No unique thoughts

At this point, I turned to the internet. What was the highest score anyone had gotten in the game, and how did 539 stack up? Quickly, I found this FANTASTIC blog post by Craig Polley which everyone should read, along with his other fascinating content on the blog (which by the way has been an inspiration for me to start a similar website documenting my own explorations, in the hope that someone would find them similarly interesting.)

Here, Craig described his own obsession with this problem, and quickly shattered any illusions I had about finding the strictly optimal solution. In his words:

“if every atom in the universe (≈1080) were a computer, and these computers were a million times faster than the one I am using (so ≈50 million games/second), and they had all been simulating SPL-T games >for the entire age of the universe (≈14 billion years), they could only have comprehensively explored the game tree to a depth of 100 moves.”

Even if an “optimal” solution was out of reach, though, two things in Craig’s post provided hope in being able to find some closure for this obsession. One, Craig had created a python emulator of the game with which it was possible to simulate the many millions of games that would be necessary to set a new high score. Second, thankfully Craig had given up before he implemented a meaningful playing strategy, and instead relied on strict randomness (and several days of computing time) to find his record-breaking sequence. This meant that if I encoded any kind of human strategy into the playing algorithm, I could (theoretically) blow his score out of the water pretty easily.

That naturally led to the question: what would that human strategy be, and how could it be encoded into a Python algorithm and exploited to find a high score?

3. SPL-T Strategy

The following section will be heavy on the intricacies of SPL-T and what things I found important to encode in the algorithm. If you’re not as interested in this and are more interested in algorithm implementation, feel free to skip to section 4 (though if you want a taste, the first consideration is the most interesting).

In my observations playing SPL-T, there are a variety of factors that contribute to determining whether a move is good or bad. Some moves can be good in some respects and bad in other respects, so it makes sense to come up with a variety of considerations, apply a positive or negative bonus to each move based on each consideration, and then tally up the total score of each move. The considerations (implemented in the findWeights() function within weighting.py in the repository) are as follows (click each to expand):

Using point block explosions (Most important!)

Far and away the most important consideration in SPL-T strategy is making full use of the block explosion mechanic. As touched on in the tutorial, when a block falls (i.e. a point block below it disappears) its point value gets reduced by half. Making the most of this mechanic is absolutely critical for success as the number of splits gets higher - when point blocks nominally take 800 turns to disappear, you have no chance at just waiting it out. Place that block above three or four point blocks that are about to explode, however, and that wait becomes more like 50-100 turns, soon enough that by the time you run out of space elsewhere on the board, this cluster of point blocks will be ready to disappear and be split again.

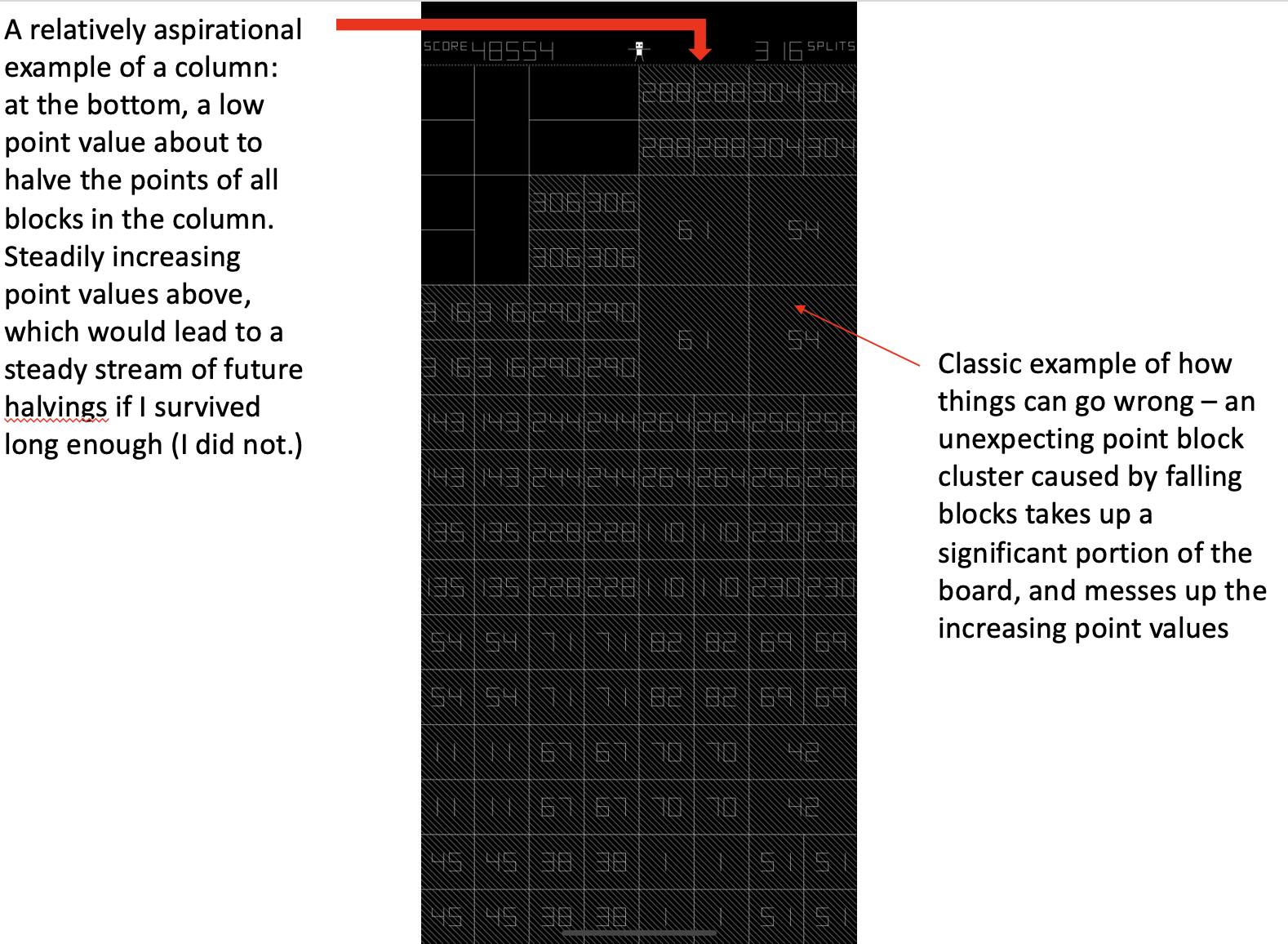

In an ideal world, your board should look something like the below screenshot - a bottom row full of low point blocks, followed by point blocks of ever increasing value - as high value blocks are created near the top of the board, they're steadily halved until they reach the bottom of the board several dozen turns later, with a low value and ready to explode and continue the cycle.

From an algorithmic perspective, this means that any time a point block is about to explode, you should be trying hard to create a new point block above it so that it can take advantage of this almost immediate halving. There are several factors to consider here.

One, the more imminently this explosion is happening, the higher the algorithm should prioritize creating point blocks here. If there are many turns before the block actually explodes, the algorithm may want to prioritize other things.

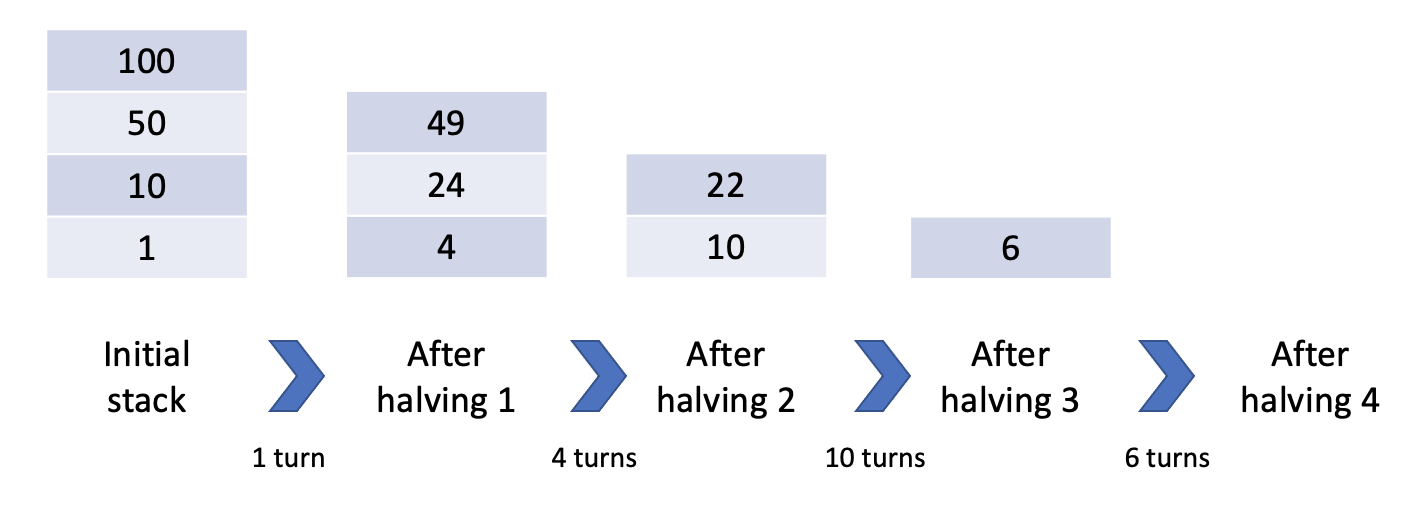

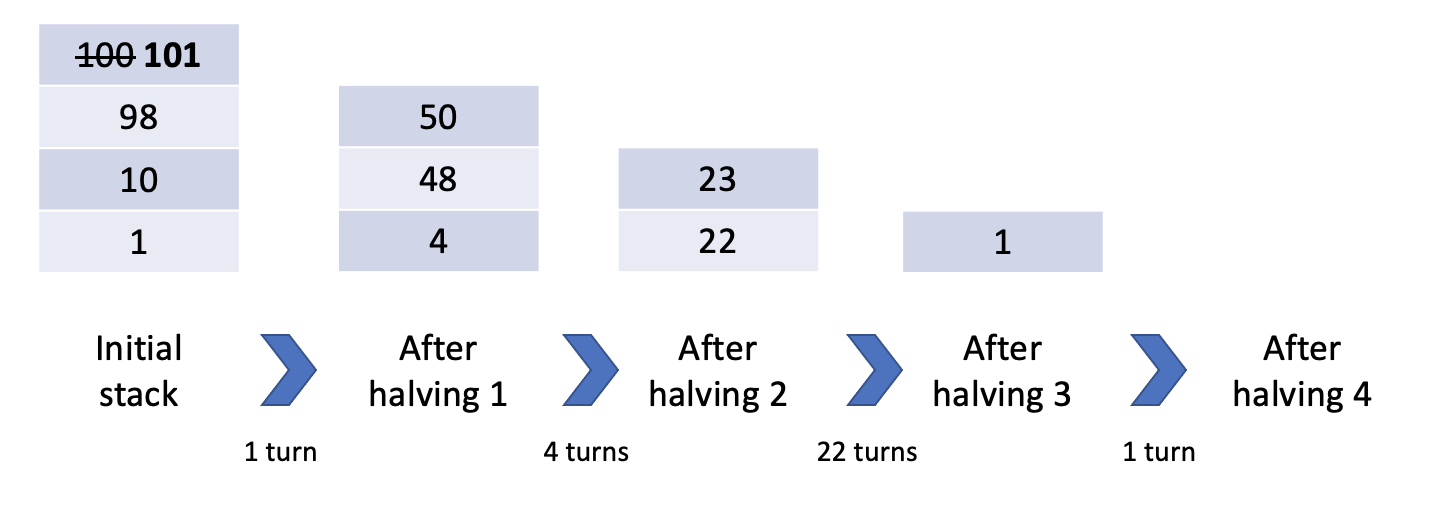

Two, not all halvings are created equal. Clearly, it's in your best interest to maximize the separate number of times points get cut in half, but sometimes the benefit of an imminent explosion has already been claimed. To motivate this, let's look at the following example. Say you're about to create a cluster of 100 point blocks on a stack of blocks with points 1 - 10 - 50: this is great! Point blocks placed above this new cluster will be halved *four* whole times!

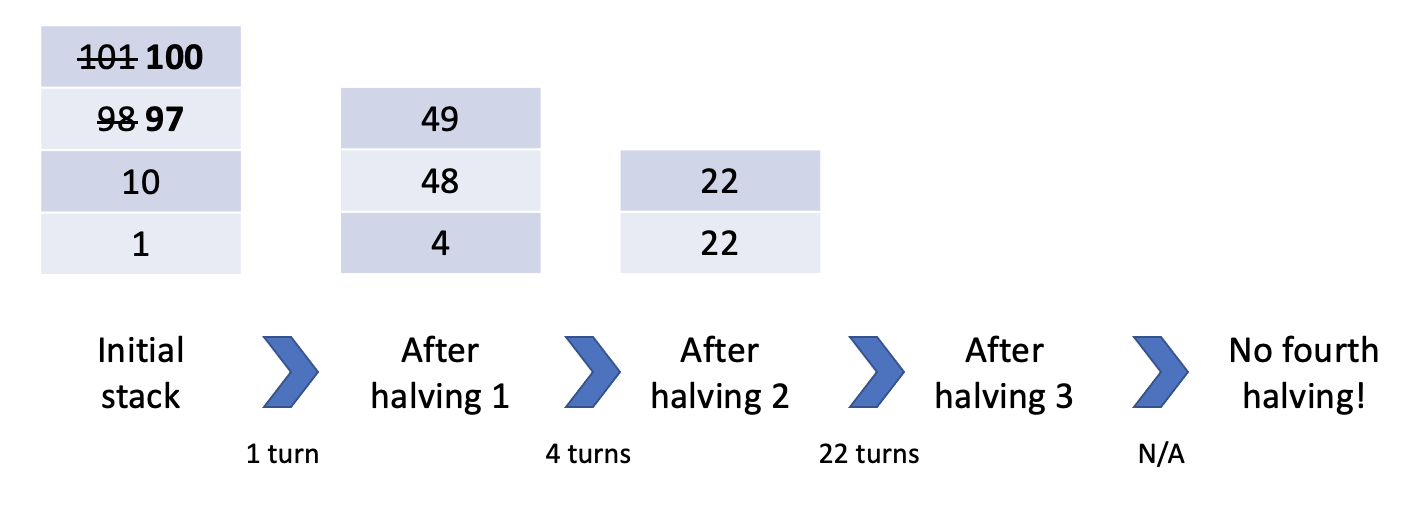

However, consider instead you just recently created a point block in this column, meaning the stack was something like 1 - 10 - 98:

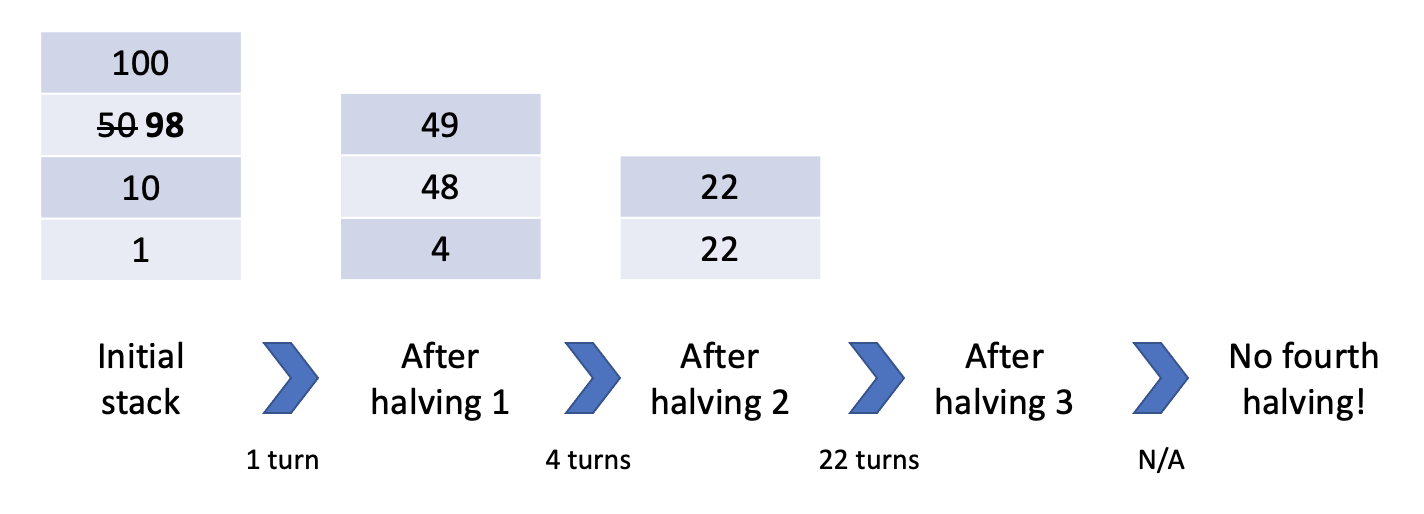

Because you so recently created a point block in this column, you're losing the benefits of this explosion, and future blocks will only be halved *three* times rather than *four*. This can make quite a large difference when initial point values are in the high hundreds. If instead you had just "waited" one turn and created a point block with a value of 101, you would again reap the benefits of four halvings:

Because of the way rounding works in SPL-T (halvings in SPL-T round down, except for 2 i.e. if a block with 5 points falls, its new value is 2. If a block with 2 points falls, its new value is 1.), it's surprisingly hard to pin down the exact circumstances that a new point block will cause a new halving. For example, a distance of three from the last point block in the column doesnt always save you! Consider:

Infuriatingly, I was never quite able to come up with a clean mathematical formula to work this out given a stack of point blocks, and instead I just wrote a function to do this for me somewhat manually (`doesPointBlockCauseNewHalving()` in `weighting_new.py`), but if I've learned anything from my personal projects it's that there's always someone out there who tore their hair out over the same exact problem, so there's probably an obscure math paper from 1630 which deals with this issue. This problem can get quite complex, especially with blocks of multiple widths on the board, so I wrote a algorithm for this in `weighting_new.py` which works in 99% of cases, but concedes that in a few edge cases it won't be possible to determine, and simply says that no new halving will be created.

In the end, after all this agonizing about an exact function for new halvings, the weighting algorithm with my initial approximation to determine if a new halving was created (if the difference between the next highest is greater than 2

In summary, the algorithm really only cares about prioritizing creating point blocks above an imminent explosion if it'll get a new halving out of the deal. If so, the positive weight for the move will be quite significant, but if creating a new point block won't create a new halving, the algorithm prefers to hold off and try to finesse another halving.

Finally, even if the given move won't create point blocks, if the algorithm notices that a block is exploding pretty soon in a column, it should start making splits in this column, so that eventually a point block cluster will be able to be created.

Split type imbalance

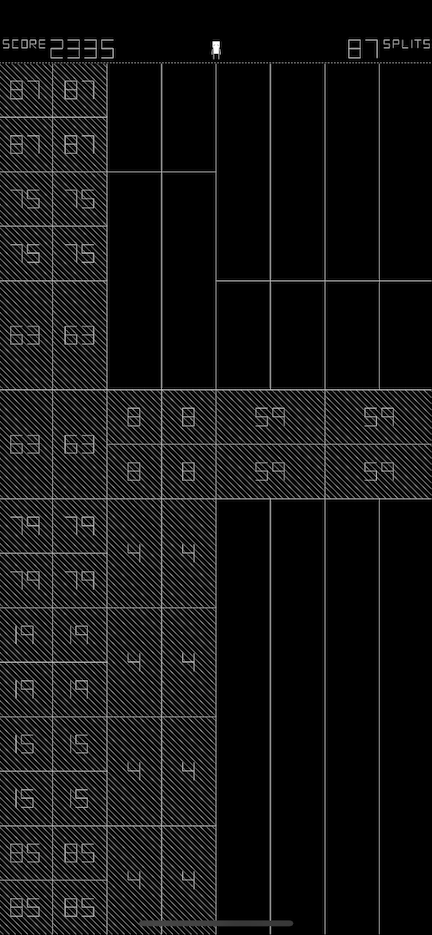

One of the first ways you'll lose when picking up the game of SPL-T is by messing up the ratio of vertical to horizontal splits on the board. For example, on the following board, there are plenty of spots left on the board, but no places left to make vertical splits:

Especially problematic on this board is the bottom right corner. By creating such thin vertical blocks, a large amount of horizontal split opportunities are created (14 in some cases!) This is good in the scenario that you're running out of horizontal splits, but if you already have too many places to split horizontally, this is really bad. In an ideal world, you'd keep the board looking pretty even, with no lopsided vertical or horizontal blocks.

Additionally, the more splits there are available, the less urgent this requirement is, as youll have some time to even things out later. Thus, we provide a positive or negative bonus when decreasing or increasing the split type imbalance, scaled by the number of splits remaining. This can scale from a pretty minor effect when it's only mildly increasing the imbalance/when there's plenty of space left, all the way up to the fully decisive consideration.

Block height

Another, generally quite minor, consideration is that when you have a choice, you'd prefer to be splitting blocks that are lower on the board. This is for the simple reason that boxes that are lower on the board have the opportunity to halve the point value of more blocks above them.

Point block size

Generally, you want to create point blocks that are smaller in size - creating larger point blocks means locking up larger parts of the board from being able to be used for splits.

Of course, there are times when this is necessary (i.e. if a block is about to be split below, it's often better to just go ahead and create larger point blocks which dissapear twice as quickly, rather than waiting for smaller point blocks which stick around forever.)

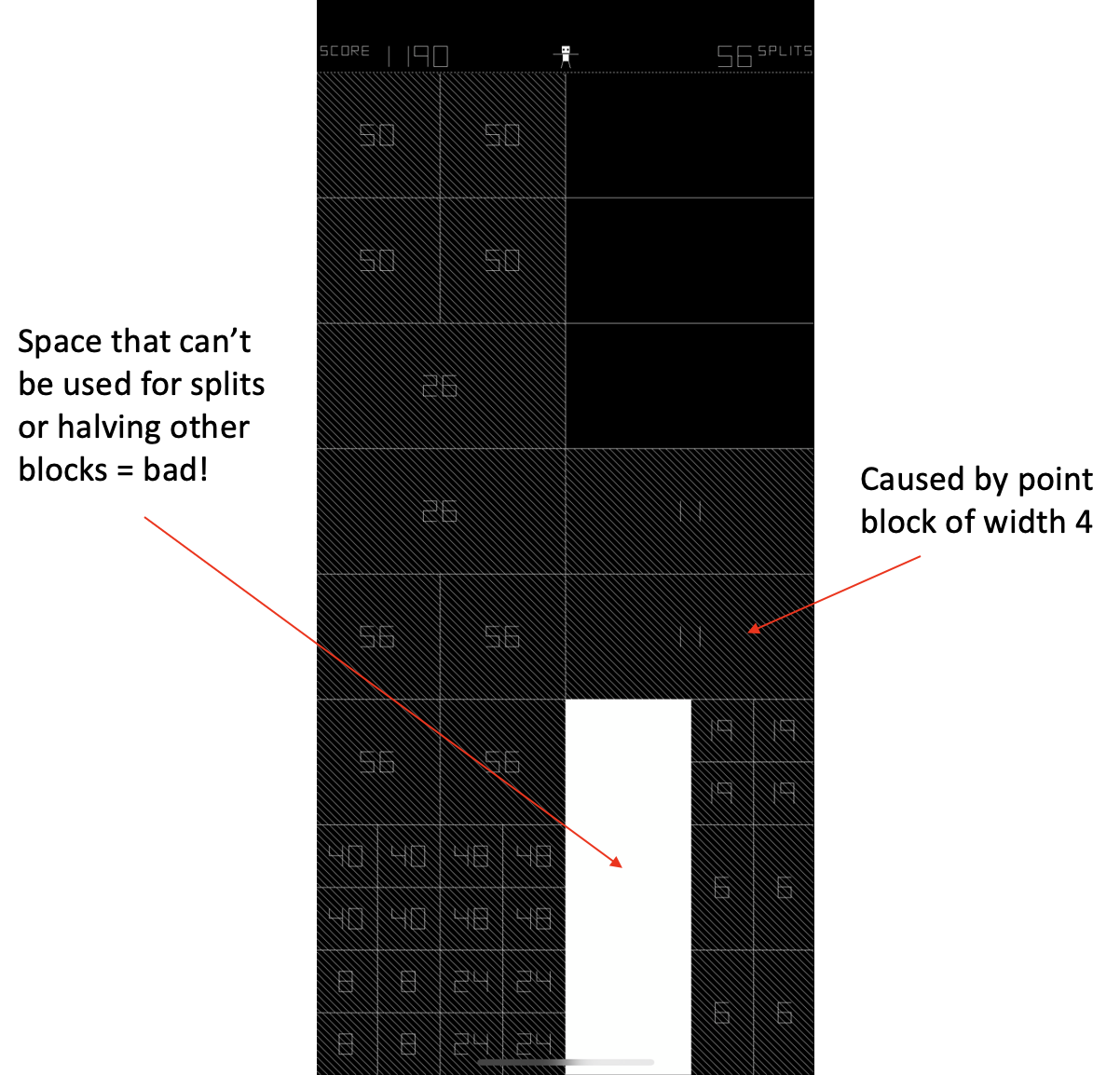

Wide point blocks

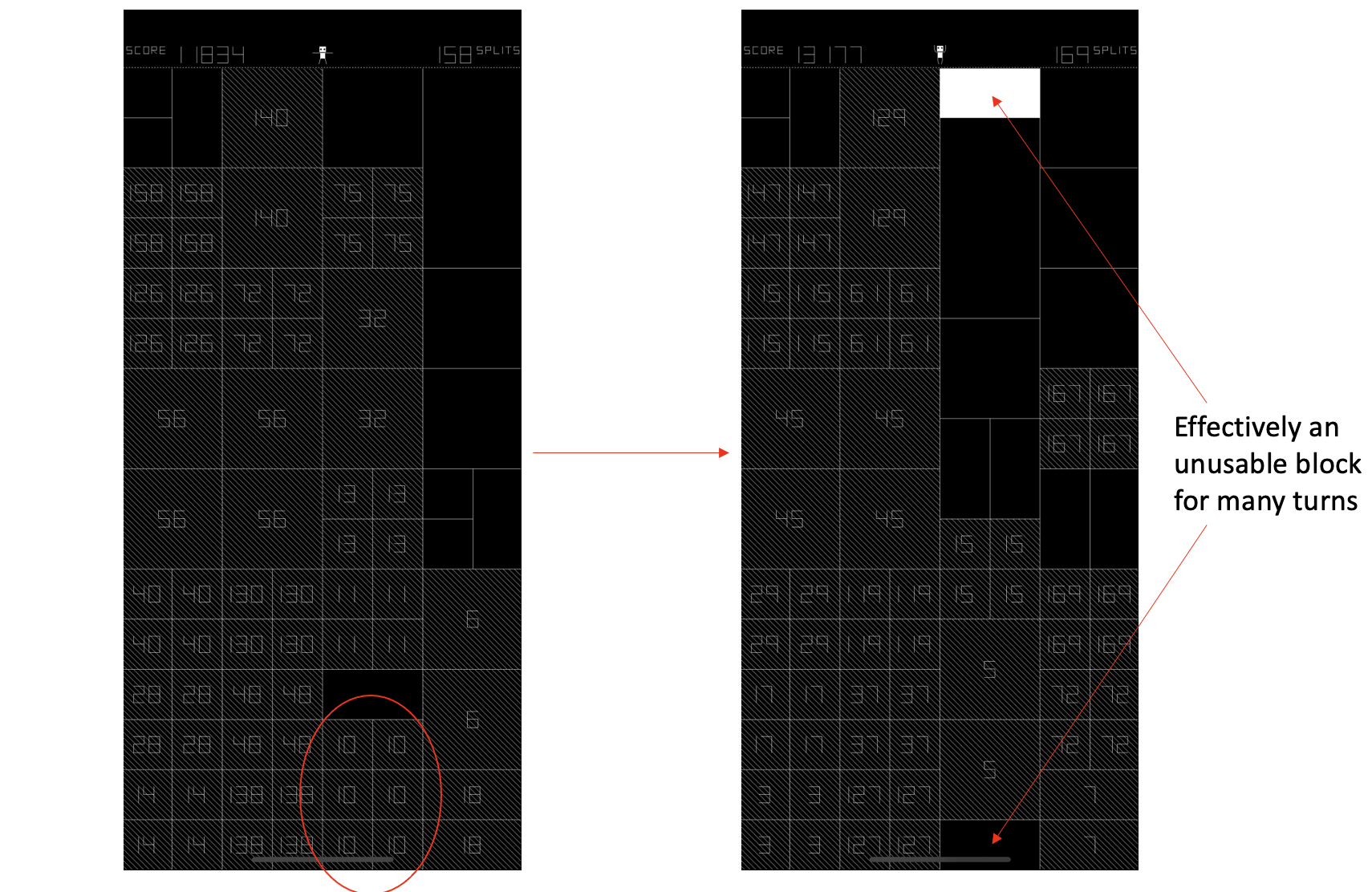

Creating wide point blocks can often block off large sections of the board, meaning that this area can no longer be used to house splits or point blocks which will eventually explode and halve other blocks on the board. See image below:

Clusters of 6+ point blocks

Typically, clusters come in groups of 4. Sometimes, however, you'll mess up and create 6 point blocks in one go. This can, as shown in the image below, lock out entire blocks for a large number of turns and as such is penalized very heavily.

Edge cases/tweaks

There are a variety of small edge cases addressed and tuning tweaks that were made after iterating on algorithm-generated games. Again, I'd point you to `weighting.py` for the full weighting codebase.

4. Probabilistic Weighting Algorithm

My initial strategy was as follows: develop an algorithm which assigns a score to each move, based on the variety of factors detailed above. For example, if a move is directly above a block that’s about to split, a positive number is added to the score. If that move would mess up the ratio of horizontal to vertical splits on the board, a negative number is added to the score. After each move has been scored for all considerations, you add up all the scores and have a clean number value corresponding to the quality of each move. Theoretically, the best move would be the one with the highest score, but even after tuning and adding every consideration I could think of to the algorithm, following the algorithm’s recommendations deterministically led to a respectable but not-good-enough 543 splits. I was expecting this - with such a massive search space, it seemed clear that adding in some element of randomness was essential to achieve the best score and correct for any errors in the algorithm.

Thus, rather than picking the move with highest score straight up, I attempted to use quality as an influence on the probability of choosing a given move. To be precise, moves were chosen randomly, with move i of n options being chosen with probability:

where si is the score of move i. (This algorithm is implemented in weighted_random.py)

Performance was… underwhelming… stalling at around 600-700 splits even after running overnight. This was unacceptable - sure, I had beaten my high score, but I was still laughably far away from the record, and I didn’t even want to calculate how many hours I had spent writing code at this point. Interestingly, I found that even Craig’s completely random algorithm outperformed mine. Sure, the algorithmic play started better, but quickly plateaued.

This was mindboggling to me after all the effort and human knowledge that I had poured into the algorithm. After looking at the number of simulated games over time, though, the root cause was clear - the algorithm was performing better on a per-game basis, but with all the computation necessary to calculate a weight for each box, the computer was able to simulate so many less games. This meant that the algorithm performed worse overall.

Well, I thought, if I was expending so many computational resources to calculate the exact correct move, it seemed I should use this information more. Furthermore, the way the weights were designed didn’t necessarily even lend themselves to probabilities - a box with weight 100 is significantly more attractive of an option than a box with weight 50, and as such should probably be picked more than 67% of the time when offered a choice between the two options. Thus, I wanted to switch to using the algorithm-selected box as a ground-truth correct move.

5. Final Algorithm: “ParanoidPlay”

One major limitation of the weighting algorithm as it currently stands is that it only knows if a split will cause a point block cluster based on the blocks on the board at that time - it has no knowledge of any blocks falling. (This limitation is there for technical reasons - calculating the new state of the board after falling blocks, for each candidate move, would be extremely computationally expensive.) This meant that sometimes the algorithm would make a conservative split, but falling blocks would cause large point blocks to be created unexpectedly, and cause an early end to the run.

Inspired by this common occurrence, the idea for the ParanoidPlay algorithm was born. So many runs are lost by creating point blocks that end up being too large, but on the other hand, large point blocks are sometimes necessary to keep a chain of halvings alive. What if the algorithm still allowed for large point blocks to be created, but was “paranoid” and kept a record of each time it did so? If later the board filled up, the algorithm could return to this decision and avoid it in the future.

Adding to this, sometimes split decisions are very close, with weights differing by only 2 or 3 weighting points. In these cases, it’s very possible that the best split was actually the one that the algorithm determined to be, say, 2 points worse. Anytime the algorithm made a tough decision of this kind, it could also remember that decision and choose to go the other way once losing the game with it’s standard .

These two additions led to the algorithm in randomParanoidPlay.py and defined in pseudocode below:

- Make 50 random moves at the start of the game, with probabilities biased for each move based on weight according to the formula seen earlier in the blog post (I was able to achieve 1053 splits with a beginning based solely on the algorithm, but it seemed to be in a local maximum)

- Initialize

other_option_boardsandother_option_weights, arrays of gameboards and weights respectively which correspond to different decisions that could have been made. - While there are still moves to make in the given game:

- Play the move with the highest calculated weight.

- If last split created a large cluster of point blocks (bigger than 4 1x1 blocks), set variable

split_created_big_clustertoTrue - Every other time the last split was a really close decision (weight difference between top two choices 1<diff<3), set variable

another_as_good_optiontoTrue(not every time to keep the problem computationally tractable) - If

split_created_big_clusterORanother_as_good_option, save the board inother_option_boards. Set the weight of the second best option to the weight of the best option, and then set the original best option to zero to ensure it is never chosen again. Save this edited weight array inother_option_weights

- Once out of moves, return to the board in the last index of

other_option_boards, load weights fromother_option_weights, and continue to the end of the game. Continue this process until the other option that you choose is below some level of splits (250). At this point, the decisions that the algorithm is paranoid have limited impact on the final state of the game, so reinitialize a random board and restart the process.

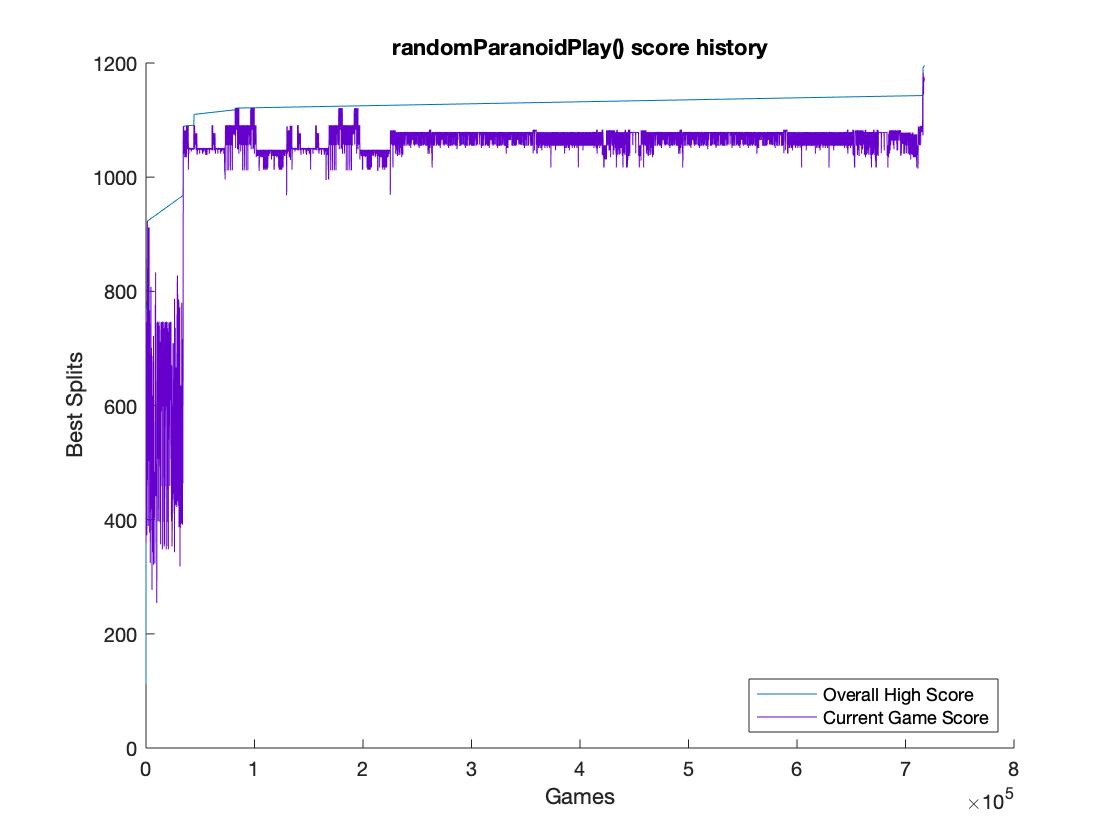

With this final algorithm assembled, the world record came into focus quickly afterwards! In just 34000 games and ~2 hours of compute, the algorithm broke the 1000 split barrier, a milestone that took Craig’s random play hundreds of millions of games to break. Given another 36 hours of computing time and 700,000 more games, the algorithm handedly claimed the world record from Jonathan Becker (@mangosquash) who stole the world record from me in the interrim.

6. Going beyond the world record - Human-AI collaboration

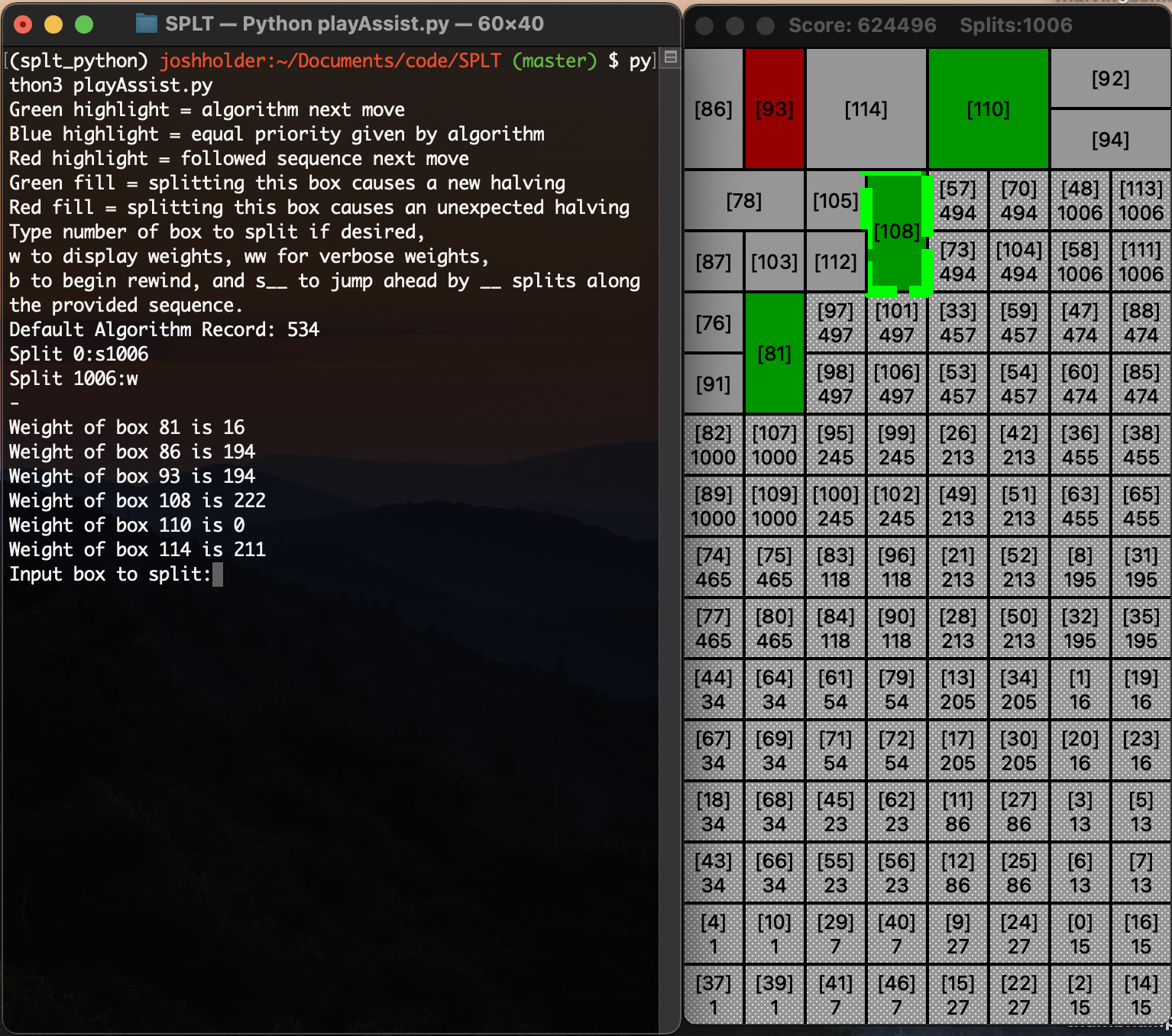

One of my goals was to develop an algorithm that could beat the world record without human interference and with limited random elements, which I achieved by reaching 1196 splits. However, throughout the process, I had observed that by infusing some actual human judgement into the algorithm, even greater results could be achieved. Thus, playAssist.py was born - this program provides effectively an enhanced user interface for playing games of SPL-T, infusing information about the algorithm recommended moves, whether a given split will cause a new halving, unexpected clusters caused by falling blocks, the ability to back undo moves, and more. An example of the UI is shown below:

Combining these capabilities with tools like the ParanoidPlay algorithm provides a powerful workflow for extending the high score even further. Once randomParanoidPlay.py provides a high score sequence, a human can go inspect the sequence, make a couple of key adjustments using playAssist.py, feed this new sequence back into randomParanoidPlay.py, and let the algorithm explore from this new improved state. In just a few minutes, I was able to take the high score achieved using purely algorithmic means (1196 splits) and extend it to 1208 splits. These sequences can be found in the sequences folder in the repository, and verified by following along with replay.py on your own device.

Going even further is no doubt possible, but at this point, unless someone unseats me again, I think I’ve learned as much as I can from this game, and am ready to move onto other pursuits. As far as a I can tell, the theoretical maximum number of splits could be as high as 3700 splits (7 halvings, 14 turns to wait once all halvings have occurred), but practically this extremely difficult. If a block with 3700 points is ever placed in a column that is going to be halved less than 6 times, it will never dissapear again for all intents and purposes. Anyone who has played SPL-T knows how unrealistic it is to achieve 6 halvings on every single block. In my estimation, the absolute optimally high number of splits probably lies ~1800.

If you read this far, thank you! Please feel free to reach out with any questions about the repository via email - I’d happily walk anyone through the algorithms if it meant I could find someone to talk to about the intricacies of SPL-T.

A Note on Machine/Reinforcement Learning as Applied to SPL-T

It was during this exploration that I encountered DeepMind’s seminal paper on AlphaZero. Instantly, I recognized the potential of the AlphaZero algorithm to be applied to SPL-T - after all, compared to a two-player game on a 19x19 board, a single player game on an 8x16 board seemed doable. Furthermore, it would allow me to go beyond my feeble SPL-T ability - by using a human-“expert” generated algorithm, performance would be inherently limited by my capabilities. By using reinforcement learning, my own limitations would no longer apply and the algorithm could get closer to the true ceiling of perfect SPL-T play.

I actually implemented a full AlphaZero-style reinforcement learning pipeline for the game here. My naïvete was quickly stifled by the enormity of the computational complexity of the problem, and a lack of experience and computing resources, but contained in that repository is a model that I think actually begins learning (albeit almost imperceptibly slowly)! In the future, I hope to do a full writeup on these efforts as well, and use my bespoke weighting algorithm to jumpstart training and hopefully see some results, à la AlphaGo (the predecessor of AlphaZero).