Solving Nim (The Matchstick Game)

A tough loss at a common grade-school pen and paper game while distracted in class led to me getting way more distracted in class, and spending the weekend writing an algorithm which could algorithmically determine the optimal move in games of Nim (repository here). This project was my first real foray into independent computer science passion projects.

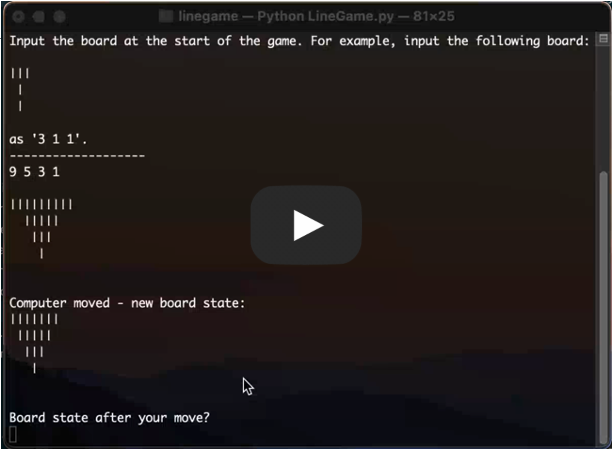

A visual representation of the power of the final Nim AI.

1. Background/Rules of the Game

Recently, while getting off task in lecture, I came across a simple pen and paper game you might recognize from grade school (later, I realized the game was called Nim). In case you’re not familiar, feel free to look up the rules or glance at my attempt at an explanation. The premise is simple - the game starts with a board like this:

I I I I I

I I I

I

The first player can cross out any amount of lines they want in a given row. For example, I might cross out two lines in the first row, leaving the following:

I I I I I

I I I

I

From here, the next player may cross out any amount of lines they want, provided they are in the same row and not separated by any strikethroughs already. The last player to strike through a line loses.

These would be valid board states arising after the second player moves:

I I I I I

I I I

I

or

I I I I I

I I I

I

But not this:

I I I I I

I I I

I

Aside on board notation going forward (click to expand):

One can imagine several ways to store a representation of a board state in a way friendly to computers. Throughout the code, I alternate between dictionary and list forms, where the following board:

would be stored as {3:1,1:2} or [3, 1, 1] as a dictionary or list respectively. For the rest of this blog post, I'll be using list notation to reference boards.

Seems simple enough, right? Well, while half-playing against my friend and half-paying attention to the lecture, I kept losing the game. This bothered me; how was I getting bested so consistently at such a simple game? Furthermore, with no random elements, one thing was clear: at any given board, there was a winning sequence. This kept gnawing at me; what was the sequence, and how could I find it?

An online search turned up no results (I only later figured out the actual name of the game) so, as any overly competitive nerd would do, I spent most of the next weekend coding an algorithm designed to beat my classmate at a game designed for middle-schoolers.

2. Generating all possible games from a given board

The first thing that I wanted to do was to figure out a way to generate all the possible games that can be played from a given board state. I didn’t yet have a clear idea of how to leverage this information to determine the winner (and winning move) for a given board, but I had a gut feeling that it would help. It seemed to me that the best way to do so would be to utilize recursion. (The fact that I had just learned recursion in class may or may not have been a factor in making this decision. No comment.)

In simple terms, I envisioned that the program would take in an input board, say:

[3, 1]

And then generate all the unique boards one could reach within one turn:

[2, 1] [1, 1, 1] [1, 1] [3] [1]

From there, the program would recursively call itself on each of these new boards, and continue until reaching the board [1] for all of the games. Along the way, the board at each step would be saved, eventually generating a list of lists of board states, or the complete collection of possible games that could arise from a given board.

After some tinkering, I was able to create code that would perform this function, located in LineGame_get_games.py in the repository.

3. Determining the winner from a given board state

With some of the groundwork laid with the function LineGame_get_games.py, it was time to actually have to figure out how to determine the winning sequence from a given board. Looking through the vast tree of possible games that could be played based on a given board configuration, one might imagine that it would be simple to figure out whether a board was a win or a loss. But when you get down to it, it’s tougher than you might expect to nail down the actual winner.

I decided to shift gears in my approach; instead of starting my search from the top at the initial board state, I decided to begin my search at the bottom of the tree instead. To do so required clearly defining what a forced win actually meant.

At the most basic level, a board is a win for one player if they can make a move and reduce the board to the state [1]. What boards can actually achieve this?

[2], [3], [4], [5] …

[1, 1], [2, 1], [3, 1], [4, 1], [5, 1] …

In this way, if you ever see one of the above boards, you instantly win - these boards are thus defined as “forced wins.” Conversely, a “forced loss” would be such a board such that no matter what move is made, a “forced win” board is reached.

Ideas for an algorithm should already be beginning to become clear, but in order for it to work, we need a generalized algorithm for generating the previous boards that can lead to a given board.

Taking the exercise above as an example, the general principle for boards which can precede another board is defined as follows:

- All boards which add some amount to an existing row in the board (i.e. [2, 1] can be reached from [3, 1], [4, 1], [2, 2], etc.)

- All boards with an entirely extra row which can be fully crossed out (i.e. [2, 1] can be reached by [5, 2, 1], [2, 1, 1], [100, 2, 1], etc.)

- All boards with a row >1 larger than two of the existing rows which can be split up (i.e. [2, 1] can be reached by [4], [5], etc.)

With this, we have all the elements necessary to create an algorithm which can optimally play Nim.

4. Final algorithm pseudocode

The following algorithm is implemented in LineGame.py. You can utilize the AI by simply running python3 LineGame.py in the command line and following the prompts, either to test your skill against the AI (hint: you lose), or to beat your friends.

- Input:

initial_board= game board in dictionary format - Initialize

forced_lossesandforced_wins, lists of board states which, when given to the agent, will always lead to a loss and a win respectively. Upon algorithm initialization, all we can say is that the board [1] is a forced loss. - Initialize

new_forced_lossesandnew_forced_wins, lists of forced losses and wins that have yet to be expanded upon. Upon algorithm initialization, [1] is the only “new forced loss” - Initialize

add_factor= 0 - while

initial_boardis not inforced_lossesorforced_wins:- if no new forced losses were found on the previous iteration:

add_factor+= 1 - else:

add_factor= 0 - for

lossinnew_forced_losses:- Find all previous boards that could’ve led to the current forced loss (using

add_factorto choose which of the infinite previous boards to add to the list), add them all toforced_winsandnew_forced_wins(the player recieving this board can just cross out the lines appropriately to reach the forced loss, and this means that these boards are forced wins) - Remove loss from

new_forced_lossesas it has now been expanded - Now you have some new forced wins!

- for

new_forced_wininnew_forced_wins:- Find the previous boards that could have led to this board,

prev_boards - for

prev_boardinprev_boards:- Generate all possible moves that can be made from the board

- If ALL possible moves are present in

forced_wins, then that is a forced loss. Add the board toforced_lossesandnew_forced_lossesand start over from the beginning.

- Find the previous boards that could have led to this board,

- Find all previous boards that could’ve led to the current forced loss (using

- if no new forced losses were found on the previous iteration: